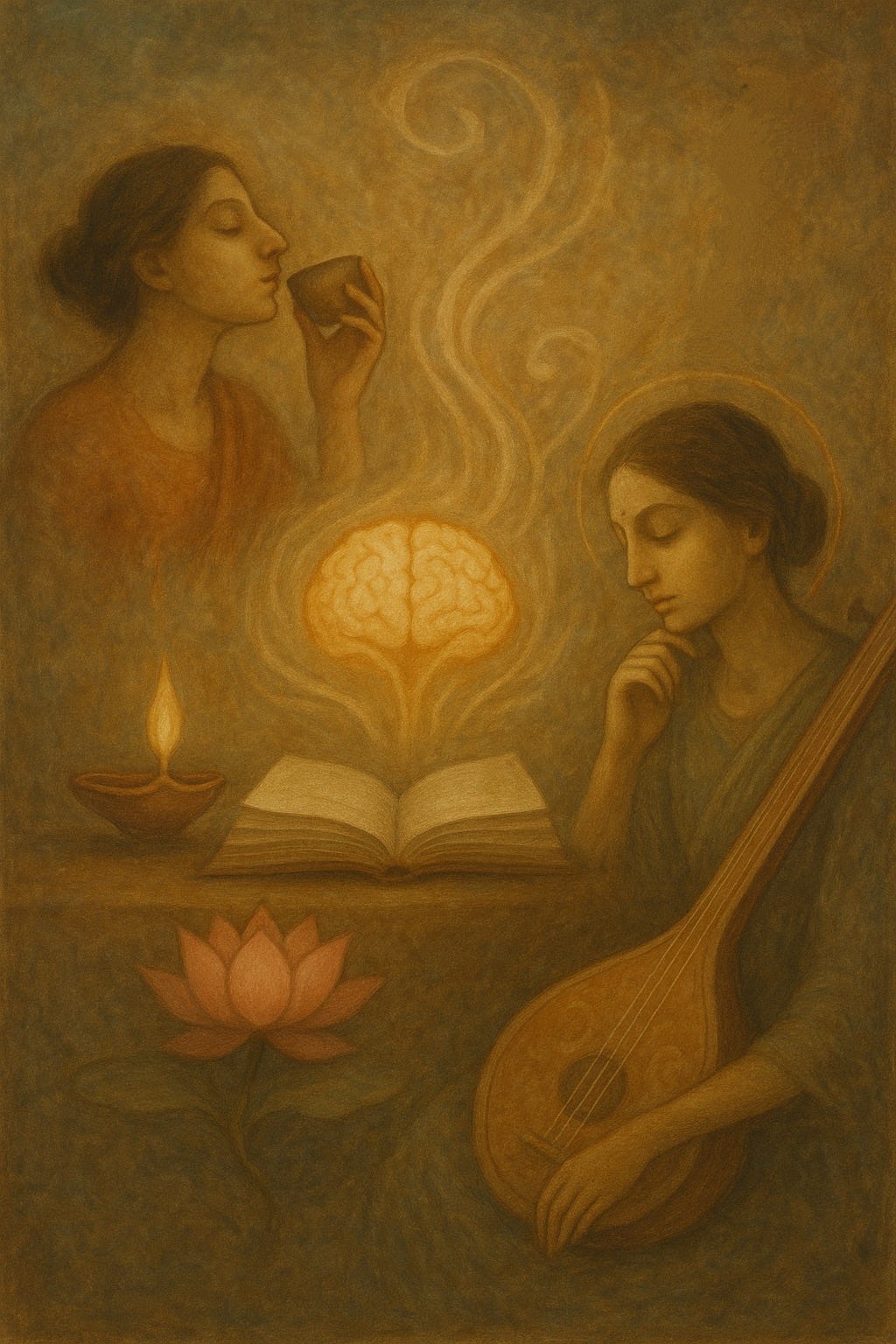

Enjoy, we must! But with Knowledge and Strength

Ignorance is bliss, but it has a bitter aftertaste

श्रेयो हि धीरः अभि प्रेयसो वृणीते

प्रेयो मन्दो योगक्षेमात् वृणीते

— Katha Upanishad 1.2.21

“The wise choose Shreya, the good, over Preya, the merely pleasant. The foolish, driven by desire, choose Preya for the sake of comfort and security.”

During my teenage years and into the early part of my working life, I often felt a subtle unease. A quiet voice within whispered that something was missing, especially whenever I went out to party or lost myself in carefree fun with friends. It wasn’t guilt, exactly. It was something deeper, like an old soul tapping me on the shoulder, reminding me that the joy I was chasing had an expiry date, that it would leave me hollow once the music stopped.

Something inside me disagreed with too much merrymaking, relentless extroversion, and a life lived only outward. And truthfully, I often wanted to silence that voice. I wanted to be fully immersed in the moment like everyone else seemed to be.

But how could I?

That voice was me — my authentic self. The part of me that saw through the illusion even when I didn’t want to.

Over the years, I stopped resisting it. I began listening. I befriended that voice and slowly understood its nature. I realized I wasn’t alone in hearing it. Many of my friends, in their thirties or sixties, have admitted to sensing something similar. Some don’t notice it until a so-called mid-life crisis hits. Others only recognize it on their deathbed. A few, blessed or cursed, depending on how you see it, awaken to it early in life.

To me, a mid-life crisis is nothing but a rude awakening, the realization that you’ve been chasing someone else’s dream, only to find it doesn’t nourish your deeper self. That’s when people panic. They feel they haven’t even started living. It’s a tragic irony but also a turning point. And I say: let the crisis come in mid-life rather than too late. For if it comes at the deathbed, what remains is not transformation but regret for the unlived life, for the missed potential, for never having asked, “What was I truly meant to do here?”

This core tension between surface-level pleasure and deeper fulfillment is not new. It was captured with poetic brilliance in the Katha Upanishad, in the dialogue between the young seeker Nachiketa and Yama, the Lord of Death[2]. When Nachiketa asks for knowledge of what lies beyond death, Yama tries to distract him with temptations: wealth, long life, celestial music, and pleasures of every kind. The Upanishad calls these Preya—the path of the pleasant, tempting, and immediate.

But Nachiketa, with startling clarity, refuses them all. He says in essence: “These pleasures decay the senses. They distract the mind. They perish. Keep them. Give me instead that which endures.” This is Shreya—the path of the good, the true, the soul-aligned.

Looking back, I now see that the voice I kept hearing in those moments of excess was my inner Nachiketa. Not a killjoy, but a subtle form of Viveka—discriminative wisdom[3]. A quiet knowing that while what I was doing was fun, it wasn’t fulfilling. That my joy wasn’t false, but it was finite.

And this is the very threshold where the Bhagavad Gita begins—not in a forest or a monastery, but on a battlefield[4]. Arjuna’s crisis is not one of morality but of perspective. He stands torn between comfort and conscience, between withdrawal and courageous action. At that moment, Krishna did not hand him commandments. He offers him drishti—a shift in perception.

Through Karma Yoga, Krishna teaches Arjuna that joy and action can coexist with wisdom and detachment, that living in the world need not mean being consumed by it, and that true enjoyment is not the avoidance of suffering but freedom from compulsion. In this way, the Upanishads and the Gita are not two separate teachings. The Upanishads light the inner fire of inquiry, and the Gita teaches how to carry that flame through the storms of life.

Shreya, then, is not the rejection of joy—it is joy with a spine. It is the kind of fulfillment that doesn’t fade the next morning. The kind that doesn’t leave you asking, “Was that it?”

It is the joy that arises when your outer life and inner self are in harmony. And that’s what I had been yearning for all along in those teenage years—not abstinence or asceticism, but alignment. It was a joy that didn’t cost me my clarity, a freedom that didn’t fog my mind.

So yes—enjoy, we must. But let our enjoyment rise from a place of knowledge and strength, not ignorance and escape. Let it be lit by the vision of the Gita, rooted in the discernment of the Upanishads. When joy flows from such a place, it leaves no bitter aftertaste. It nourishes, it strengthens, it lasts.

Sometimes, I still reach for the easier joy—the passing pleasure, the small escape. It’s human, I suppose. But there’s a quiet shift now, like a thread I can feel beneath the noise. That old voice, once inconvenient, no longer interrupts—it waits. It watches. And when I listen, even for a moment, the world feels a little more still. A little more real. I still laugh, still wander, still forget. But something in me remembers. And slowly, I return.

Katha Upanishad, 1.2.2. One of the principal Upanishads, this dialogue between Nachiketa and Yama explores the nature of the Self, death, and liberation.

Nachiketa is a central figure in the Katha Upanishad, representing youthful spiritual courage. His inquiry into the eternal truth begins when Yama offers transient pleasures, which he refuses.

Viveka (विवेक) in Vedanta philosophy refers to the power of discernment, particularly the ability to distinguish the eternal from the ephemeral.

The Bhagavad Gita, especially chapters 2–4, discusses Karma Yoga, the nature of the Self, and the need for wise action without attachment.