The Gopuram and the Burden of Doership

How the false sense of “I” exhausts itself, and what it means to live as an instrument of the Divine

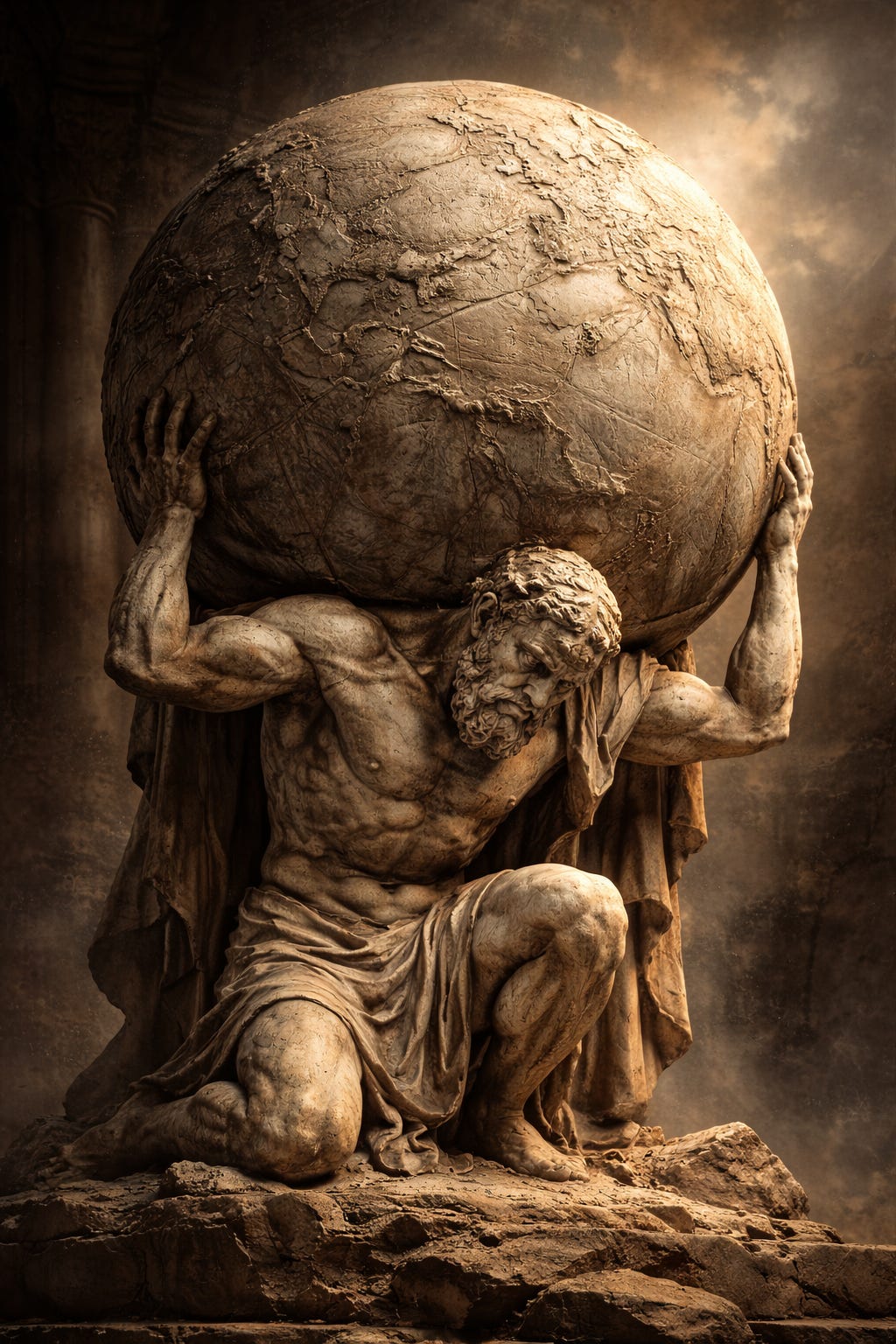

Ramana Maharishi once gave an example that quietly dismantles one of the deepest confusions of human life. He spoke of the gopuram of a South Indian temple and the pillars that appear to hold it upright. To anyone looking at the structure, it seems obvious that these pillars are bearing an enormous weight. Their posture suggests strain, effort, and responsibility. But this appearance is deceptive. The gopuram is not truly resting on the pillars. It rests on the foundations beneath it, and those foundations rest on the earth itself.

If a pillar were to believe that it alone was supporting the temple tower, it would imagine a burden that was never its own. It would tire itself unnecessarily, assuming responsibility for something that is in fact upheld by a far deeper and stronger support.

The exhaustion would not arise from the work itself, but from ignorance of the ground on which it stands.

Ramana used this image to point toward a fundamental error in human consciousness. Man imagines himself to be the doer. He believes that the weight of the world rests on his shoulders. He assumes authorship of the action, ownership of the results, and responsibility for outcomes that are ultimately not his to bear. This mistaken assumption is the true source of inner fatigue.

Real spirituality begins precisely here. It must result in transformation, and transformation is only possible when a truth is practical enough to be lived moment by moment.

At the center of the problem lies the egotistical sense of “I.” This is the “I” that claims ownership over action and says, “I act, I decide, I achieve.” This sense of doership belongs to a mind that has not yet found rest. It lives in fear, confusion, and effort because it is still searching for an anchor. Until such an anchor is found, life unfolds as a repeated cycle of striving followed by exhaustion.

What is required is not the abandonment of action, but the gradual renunciation of this false sense of agentship. This is the renunciation spoken of in the Bhagavad Gita. It is an inner renunciation, a relinquishing of ownership rather than a withdrawal from life. When this egoistical “I” discovers that it is not autonomous, that it is merely a reflection arising from a deeper Reality, something essential shifts.

At that point, one comes face-to-face with an intuition of the “Real I”. This “Real I” is spoken of as Atman, Brahman, the Self. The recognition of this Reality is called Brahmajnana, Self-realization, or enlightenment. The language varies, but the experience is singular. The individual no longer feels like an isolated agent struggling against the world. There arises a quiet certainty that one is an instrument through which a higher power operates.

Once this anchoring takes place, suffering loses its foundation. The struggles that arise from ignorance dissolve because the burden of doership is no longer assumed. Just as the pillar no longer tires itself once it knows it is supported by the earth, the individual ceases to exhaust themselves once they recognize the ground of their being.

There is another way through which this anchoring can be established, and it is equally profound. This is the path of daily devotion. Through rituals, prayer, repetition, and songs, the mind is slowly trained to relinquish its claim to independence. In devotion, one repeatedly affirms that one is not the master, but the child of God, the servant of God, or the friend of God.

This shift in language is not incidental. Bhakti works by patiently impressing this truth upon the mind. It does not shock the ego into surrender. It dissolves it through familiarity and love. Over days, months, and years, this steady remembrance achieves the same end as the path of knowledge. The difference lies only in temperament. The Jnana path can be swift and uncompromising. Bhakti unfolds gently, but with equal certainty.

In both cases, the result is the same. The egotistical “I” finds its resting place in the “Real I”, and with that, the inner turbulence comes to an end.

The ideal state that emerges from this understanding is one in which a person lives continuously with the sense of being an instrument of the Divine. Action still happens. Work continues. Decisions are made. But they arise from a different center. The joy of the realized person lies not in achievement, but in abidance in the Self. Action flows from attunement rather than anxiety.

When work arises from this inner alignment, it naturally expresses righteousness. There is no inner competition, no constant comparison, no restless ambition. What remains is a quiet contentment and a relaxed strength that does not depend on outcomes.

Different teachers have spoken of this truth using different languages. Sri Ramakrishna would say that the Divine Mother has become all cosmic principles and that She herself has become the world. Ramana Maharishi would state that Brahman alone is real and that the world is Brahman. These expressions appear different, but they resolve the same inner conflict. In both cases, the egoistical “I” finds its anchor, whether in the neuter Brahman or the feminine Divine Mother.

Living the Paradox Daily: Vivekananda’s Practical Resolution

Swami Vivekananda once expressed this entire understanding in a manner that was at once humorous, compassionate, and deeply practical. He suggested that when one is well and strong, one should know that one is backed by the Real I and live with intention, courage, and strength. And when one is unwell or weak, one should depend entirely on the Divine Mother.

This is not a contradiction but a mature application of spiritual insight to the uneven rhythms of daily life. Strengths and weaknesses are both inevitable. What matters is how one relates to them. When strength arises, it is an opportunity to act firmly from knowledge, without arrogance or fear. When weakness arises, it is an opportunity to surrender without resistance or self-condemnation.

This ability to move freely between standing in knowledge and resting in surrender is what makes spirituality livable. It allows one to remain rooted in Truth without becoming rigid, and devoted without becoming dependent. The paradox is not to be resolved intellectually, but to be inhabited consciously.

For a modern spiritual seeker, this offers a complete way of life. To know oneself as grounded in the Self when strength is available, and to lean wholly on the Divine when it is not, is to live without unnecessary strain. It is to function like the pillar that knows it is supported by the earth, performing its role fully while never imagining that the weight of the temple rests upon it.

If this image of the gopuram resonates, it is worth sitting with it quietly. To notice where, in daily life, you still assume the weight of what you were never meant to carry.

If this reflection opens something genuine, I would be glad to hear how it unfolds for you.

The gopuram example given by Sri Ramana is given in talk #63 in Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi. E.g.

Talk 63.

..... The present difficulty is that the man thinks that he is the doer. But

it is a mistake. It is the Higher Power which does everything and

the man is only a tool. If he accepts that position he is free from

troubles; otherwise he courts them. Take for instance, the figure

in a gopuram (temple tower), where it is made to appear to bear

the burden of the tower on its shoulders. Its posture and look are a

picture of great strain while bearing the very heavy burden of the

tower. But think. The tower is built on the earth and it rests on its

foundations. The figure (like Atlas bearing the earth) is a part of the

tower, but is made to look as if it bore the tower. Is it not funny?

So is the man who takes on himself the sense of doing .....

Sri Ramana Maharshi refers to the figure at the base of the temple tower.