Deifying Desire

How Vivekananda turns craving into the very engine of spiritual freedom - without killing the man for the mosquito

Many sincere spiritual seekers today do not live in monasteries. They live in boardrooms, homes, and crowded cities, constantly navigating the silent tug‑of‑war between inner aspiration and outer action. The world demands excellence, desire, and ambition, while the soul whispers of stillness, renunciation, and detachment. This tension is not theoretical; it plays out in how we work, love, parent, and dream.

Beneath it lie two deceptively simple but profoundly shaping questions:

Must one renounce the world to live a truly spiritual life?

Are personal desires inherently incompatible with spiritual growth?

I have seen some spiritual teachers speak of desire in such a harsh and dismissive way that it leaves a lasting mark on the listener. For a young seeker especially, this kind of teaching can crush the natural aspiration for abundance, creativity, and a well‑lived life. It can render the heart dry, erode compassion, and create confusion about ambition and excellence.

In some cases, it pushes people to feel guilty for being part of the world, as if striving to build, achieve, or love deeply is inherently unspiritual. This is not only misguided; it is dangerous. Such a message can unwittingly breed guilt, alienation from life, or spiritual bypassing—the avoidance of responsibility under the guise of renunciation.

At the same time, I have noticed a persistent glorification of the monastic path over the life of the engaged householder, as if the one who walks away from the world is always purer than the one who builds within it. This bias is subtle but strong in many spiritual communities, and it often leaves the sincere seeker torn between two worlds—with no real guidance on how to walk both.

I will now try to shed light on these questions through the lens of Swami Vivekananda, who in my view was the torchbearer of Hinduism to the West. He played a crucial role in modernizing its spiritual expression by clearing it of caste‑bound distortions and by softening the rigid divide between the life of a monk and that of a householder. I believe he was able to do this because he kept the focus firmly on the essential goal: the realization of one’s identity with the Atman, beyond body and mind. From this place of inner oneness all apparent distinctions dissolve. It is only from this standpoint that any spiritual teaching finds its true foundation. Anything else, however outwardly disciplined or renunciatory, becomes a change in lifestyle rather than a resolution of the deeper problem.

Our primary source is his classic Jnana‑Yoga discourse “God in Everything”.

From a single lecture, Vivekananda sketches an entire evolutionary arc of desire.

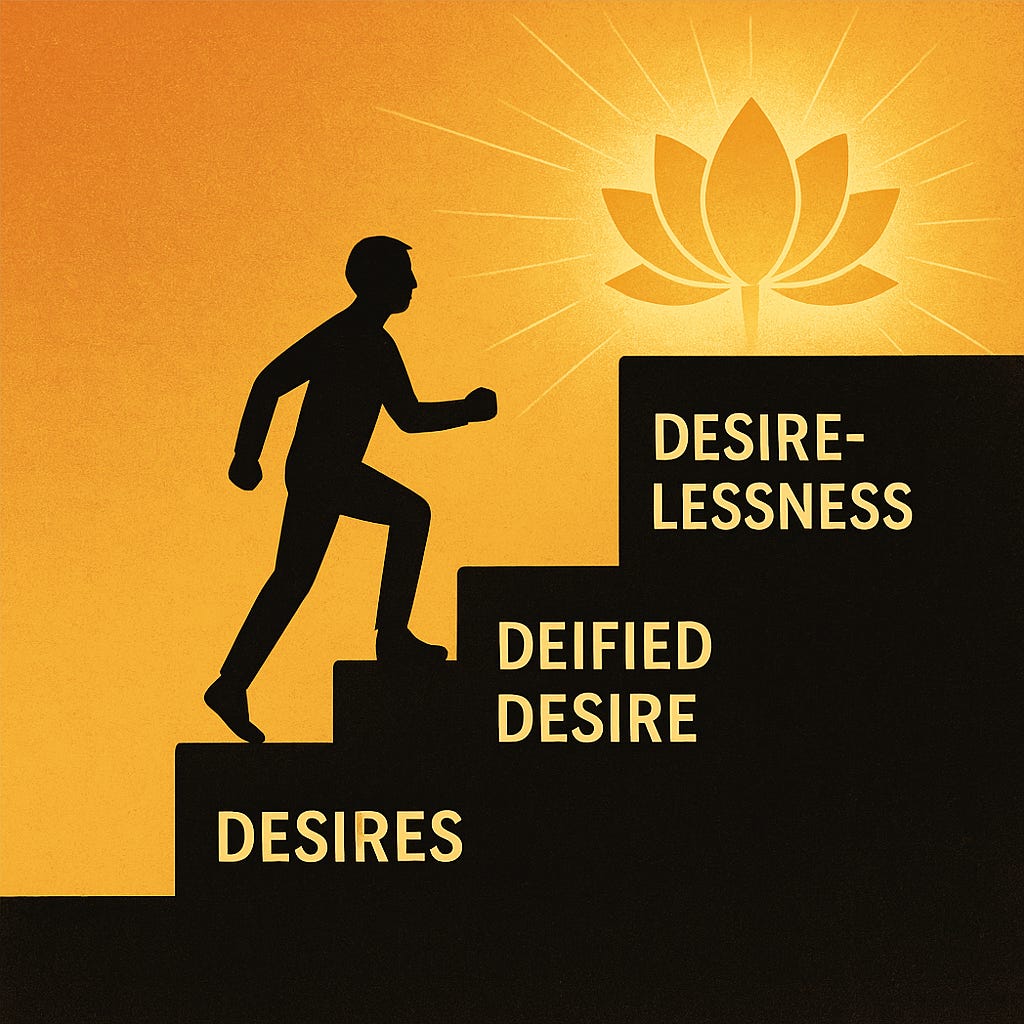

Desire as per Swami Vivekananda: A Three‑Stage Evolution

[1 ] Desire‑Driven Action

Bondage as Teacher

“What makes us miserable? The cause of all miseries… is desire.”

At the first stage, craving rules. Fulfil the urge and enjoy a momentary sweetness; miss it and suffer distress. Vivekananda nevertheless refuses to call this a mistake: chairs lack desire and therefore avoid pain—but they never evolve. Pain, born of thwarted longing, becomes the first tutor in freedom.

Inference: Stage‑1 is the kindergarten of spiritual life. Desire yanks us forward like a restless teacher: when we grab the object we taste a sugar‑rush of pleasure; when we miss it we smart with pain. That ceaseless swing is not failure but feedback. Each spike and crash sketches in bold strokes the truth that borrowed thrills fade quickly, and that lasting contentment must lie elsewhere. The very friction of wanting keeps the soul from fossilising into inertia, urging it to hunt for a deeper, steadier joy. Pain, then, is not punishment—it is a pointing finger that whispers, “Aim higher; you were made for more.”

[2] Deified Desire

Crossing the Threshold: Work as Worship, Fueled by Perseverance

Stage‑2 opens with a noticeable inner shift. The seeker is no longer spell‑bound by the pleasure‑pain pendulum of Stage‑1. The very texture of experience has changed: desires still arise, but they are felt rather than obeyed; their coming and going are watched with a new delicacy, the way a musician hears overtones that the casual listener misses. This heightened sensitivity is the fruit of every pang endured in Stage‑1; the friction of earlier cravings has polished the mind into a subtler instrument.

“God is in the desire that rises in your mind.”

Here Vivekananda insists that the impulse itself is no longer an enemy. To attack it would be, as he says, “suicidal advice, killing the desire and the man too.” Instead the seeker has learnt to recognise the current as divine and to channel it into vigorous, selfless action:

“So work, says the Vedanta, putting God in everything, and knowing Him to be in everything. Work incessantly, holding life as something deified, as God Himself… Thus knowing, we must work—this is the only way, there is no other.”

This turning of energy marks the decisive break with Stage‑1. Whereas before the mind lunged outward for fulfilment, it now pivots inward, seeking to offer rather than to acquire. Such consecrated effort must be lifelong:

“Desire to live a hundred years, have all earthly desires, if you wish, only deify them, convert them into heaven. Thus working, you will find the way out.”

Against any slide into lethargy he keeps repeating the need for dogged resolve:

“Perseverance will finally conquer. Nothing can be done in a day.”

“This Self is first to be heard, then to be thought upon, and then meditated upon.”

“Fill the mind with the highest thoughts… Never mind failures; they are quite natural, they are the beauty of life… Hold the ideal a thousand times, and if you fail a thousand times, make the attempt once more.”

And he illustrates how quickly our lofty ideals can collapse under pressure:

“We think highly of humanity… but when the ‘dogs’ of trial and temptation bark, we are like the stag in the fable.”

Failures still occur, and Vivekananda illustrates how old reflexes snap back when “the dogs of trial and temptation bark.” Yet the very sting of those lapses now quickens resolve instead of deepening despair. The seeker rises, re‑offers the impulse, and returns to the labour of love, knowing that inert objects “have no desire and they never suffer; but they never evolve.”

“The walls have no desire and they never suffer; but they never evolve.”

Inference: Stage‑2 is a forge kept hot by continuous, God‑centered effort. The seeker hoists the world as an altar, returns to work after every stumble, and slowly transmutes desire into selfless love. This is the stage which practically amounts to maintaining rigor in spiritual practices in daily life - whether it is of devotional or of knowledge temprament. This is the first time in the life of a person where daily life meets spiritual enquiry and meditation. And this is a stage which requires perseverance and repeated practice.

The subtle shift from Stage-1 to Stage-2

Motivation changes. In Stage-1 the only imagined exit from restlessness is to get the object; in Stage-2 the seeker already knows that ownership cannot yield lasting peace and therefore chooses to sanctify the impulse instead of obeying it.

Perspective widens. The same desire now appears as “God … in the desire that rises in your mind” - one more wave of divine energy to be handled, not chased or suppressed.

[3] Spontaneous Desirelessness

The Seer’s Effortless Joy

Stage‑3 dawns rather than begins; it is the natural afterglow of long, consecrated effort. Vivekananda signals the arrival point with unambiguous clarity:

“When we have given up desires, then alone shall we be able to read and enjoy this universe of God.”

The mind, once pulled outward by craving, now rests luminous and undisturbed. The world remains exactly as it was—the colours, the bustle, the daily commerce—but its grip has vanished. He clinches the contrast with his picture‑gallery vignette:

“Who enjoys the picture, the seller or the seer? … The seller is busy with his accounts; the seer has no desire to call the picture his own.”

Here the merchant‑mind still tallies profit and loss, while the seer‑mind beholds beauty for its own sake. Desirelessness is thus not a forced vacancy but an overflow: a quiet fullness that needs nothing added. Even the idea of “mine” has dropped away; the universe is experienced as a single, seamless Self.

Earlier he lamented our blinkered state: “We are dying of thirst sitting on the banks of the mightiest river… Here is the blissful universe, yet we do not find it.” Stage‑3 is the thirst finally quenched. Vivekananda insists that such realisation is possible because the mine of bliss is always present:

“Many do not know what an infinite mine of bliss is in them, around them, everywhere; they have not yet discovered it.”

In Stage‑3 that discovery becomes living fact; the mine lies open, and life flows without friction or compulsion. Work may still happen (Vivekananda himself remained intensely active), yet output is spontaneous, like a song rising unbidden.

Inference: Spontaneous desirelessness is freedom in the midst of form. The seeker no longer strives to see God in everything; he simply sees, because nothing clouds the vision. The world, once a marketplace of hopes and fears, has transmuted into a pure painting, a joy appreciated moment by moment without a single urge to own or improve it.

Why This Lens Matters

Our age alternates between glorifying relentless hustle and romanticising total retreat. Vivekananda charts a third possibility: harness desire without being harnessed by it.

Desire is the engine of evolution; chained to ego it hurts, offered to the Divine it purifies, and when its work is done it falls away, leaving a quiet, effortless joy. That is the trajectory etched into God in Everything—an emancipated vision that neither denies the world nor is dented by it.

“Desire to live a hundred years… only deify them, convert them into heaven. Thus working, you will find the way out.”

May this three‑stage arc serve as a clear lens for anyone who stands between aspiration and ambition, seeking a path that is fully human and fully divine.

Conclusion — Keeping the Baby, Draining the Bathwater

Returning to the two opening questions — Must one renounce the world? and Are personal desires inherently incompatible with spiritual growth? — Vivekananda’s answer is a resolute No on both counts, but a No grounded in reason rather than sentiment.

Renouncing the world wholesale is like killing the man to get rid of the mosquito. He calls such advice “suicidal,” because it would destroy the very arena where evolution unfolds. The right move is to cleanse, not to cancel; to keep the baby (dynamic life) while draining the bathwater (selfish craving).

Declaring desire inherently evil throws away the most potent engine of progress. When deified, the same force propels selfless work and ultimately burns itself out in spontaneous freedom. The default, knee‑jerk “give it all up” response is, in Vivekananda’s view, a triumph of feeling over rational insight - a weakness to which religions too often succumb.

Thus the lecture offers a rational middle way:

Work in the world, sanctify desire, persevere without possessiveness.

Anything less is either cowardice dressed as piety or feverish grasping masked as progress. Only this balanced path honours both the head and the heart, leading finally to the seer’s effortless joy.

Very well written article. It beautifully connected and clarified the two philosophies for me i.e., renunciation is unnecessary for spiritual growth, and seeing god in everything. I have known both for long but needed some disambiguation. This post was definitely helpful.

Really well thought out summary of Swamiji's lecture "God in everything" based on Isha Upanishad. You have extracted the essence of this lecture very nicely. Very good ideas, great articulation and inspired writing. You have some gem of phrases in here. Loved the graphic. One of you best blogs.

Thousands of years earlier, Sri Krishna offered the same ladder in Bhagavad Gita with desire replaced by action or work :)